Over the last few years, we’ve seen an increase in projects and initiatives to speed up networking in Linux. Because the Linux kernel is slow when it comes to forwarding packets, folks have been looking at userland or kernel bypass networking. In the last few blog posts, we’ve looked at examples of this, mostly leveraging DPDK to speed up networking. The trend here is, let’s just take networking away from the kernel and process them in userland. Great for speed, not so great for all the Kernel network stack features that now have to be re-implemented in userland.

The Linux Kernel community has recently come up with an alternative to userland networking, called XDP, Express data path, it tries to strike a balance between the benefits of the kernel and faster packet processing. In this article, we’ll take a look at what it would take to build a Linux router using XDP. We will go over what XDP is, how to build an XDP packet forwarder combined with a BGP router, and of course, look at the performance.

XDP (eXpress Data Path)

XDP (eXpress Data Path) is an eBPF based high-performance data path merged in the Linux kernel since version 4.8. Yes, BPF, the same Berkeley packet filter as you’re likely familiar with from tcpdump filters, though that’s now referred to as Classic BPF. Enhanced BPF has gained a lot of popularity over the last few years within the Linux community. BPF allows you to connect to Linux kernel hook points, each time the kernel reaches one of those hook points, it can execute an eBPF program. I’ve heard some people describe eBPF as what Java script was for the web, an easy way to enhance the ’web’, or in this case, the kernel. With BPF you can execute code without having to write kernel modules. XDP, as part of the BPF family, operates early on in the Kernel network code. The idea behind XDP is to add an early hook in the RX path of the kernel and let a user-supplied eBPF program decide the fate of the packet. The hook is placed in the NIC driver just after the interrupt processing and before any memory allocation needed by the network stack itself. So all this happens before an SKB (the most fundamental data structure in the Linux networking code) is allocated. Practically this means this is executed before things like tc and iptables.

A BPF program is a small virtual machine, perhaps not the typical virtual machines you’re familiar with, but a tiny (RISC register machine) isolated environment. Since it’s running in conjunction with the kernel, there are some protective measures that limit how much code can be executed and what it can do. For example, it can not contain loops (only bounded loops), there are a limited number of eBPF instructions and helper functions. The maximum instruction limit per program is restricted to 4096 BPF instructions, which, by design, means that any program will terminate quickly. For kernel newer than 5.1, this limit was lifted to 1 million BPF instructions.

When and Where is the XDP code executed

XDP programs can be attached to three different points. The fastest is to have it run on the NIC itself, for that you need a smartnic and is called offload mode. To the best of my knowledge, this is currently only supported on Netronome cards. The next attachment opportunity is essentially in the driver before the kernel allocates an SKB. This is called “native” mode and means you need your driver to support this, luckily most popular drivers do nowadays.

Finally, there is SKB or Generic Mode XDP, where the XDP hook is called from netif _ receive _ skb(), this is after the packet DMA and skb allocation are completed, as a result, you lose most of the performance benefits.

Assuming you don’t have a smartnic, the best place to run your XDP program is in native mode as you’ll really benefit from the performance gain.

XDP actions

Now that we know that XDP code is an eBPF C program, and we understand where it can run, now let’s take a look at what you can do with it. Once the program is called, it receives the packet context and from that point on you can read the content, update some counters, potentially modify the packet, and then the program needs to terminate with one of 5 XDP actions:

XDP_DROP

This does exactly what you think it does; it drops the packet and is often used for XDP based firewalls and DDOS mitigation scenarios.

XDP_ABORTED

Similar to DROP, but indicates something went wrong when processing. This action is not something a functional program should ever use as a return code.

XDP_PASS

This will release the packet and send it up to the kernel network stack for regular processing. This could be the original packet or a modified version of it.

XDP_TX

This action results in bouncing the received packet back out the same NIC it arrived on. This is usually combined with modifying the packet contents, like for example, rewriting the IP and Mac address, such as for a one-legged load balancer.

XDP_REDIRECT

The redirect action allows a BPF program to redirect the packet somewhere else, either a different CPU or different NIC. We’ll use this function later to build our router. It is also used to implement AF_XDP, a new socket family that solves the highspeed packet acquisition problem often faced by virtual network functions. AF_XDP is, for example, used by IDS’ and now also supported by Open vSwitch.

Building an XDP based high performant router

Alright, now that we have a better idea of what XDP is and some of its capabilities, let’s start building! My goal is to build an XDP program that forwards packets at line-rate between two 10G NICs. I also want the program to use the regular Linux routing table. This means I can add static routes using the “ip route” command, but it also means I could use an opensource BGP daemon such as Bird or FRR.

We’ll jump straight to the code. I’m using the excellent XDP tutorial code to get started. I forked it here, but it’s mostly the same code as the original. This is an example called “xdp_router” and uses the bpf_fib_lookup() function to determine the egress interface for a given packet using the Linux routing table. The program then uses the action bpf_redirect_map() to send it out to the correct egress interface. You can see code here. It’s only a hundred lines of code to do all the work.

After we compile the code (just run make in the parent directory), we load the code using the ./xdp_loader program included in the repo and use the ./xdp_prog_user program to populate and query the redirect_params maps.

#pin BPF resources (redirect map) to a persistent filesystem

mount -t bpf bpf /sys/fs/bpf/

# attach xdp_router code to eno2

./xdp_loader -d eno2 -F — progsec xdp_router

# attach xdp_router code to eno4

./xdp_loader -d eno4 -F — progsec xdp_router

# populate redirect_params maps

./xdp_prog_user -d eno2

./xdp_prog_user -d eno4Test setup

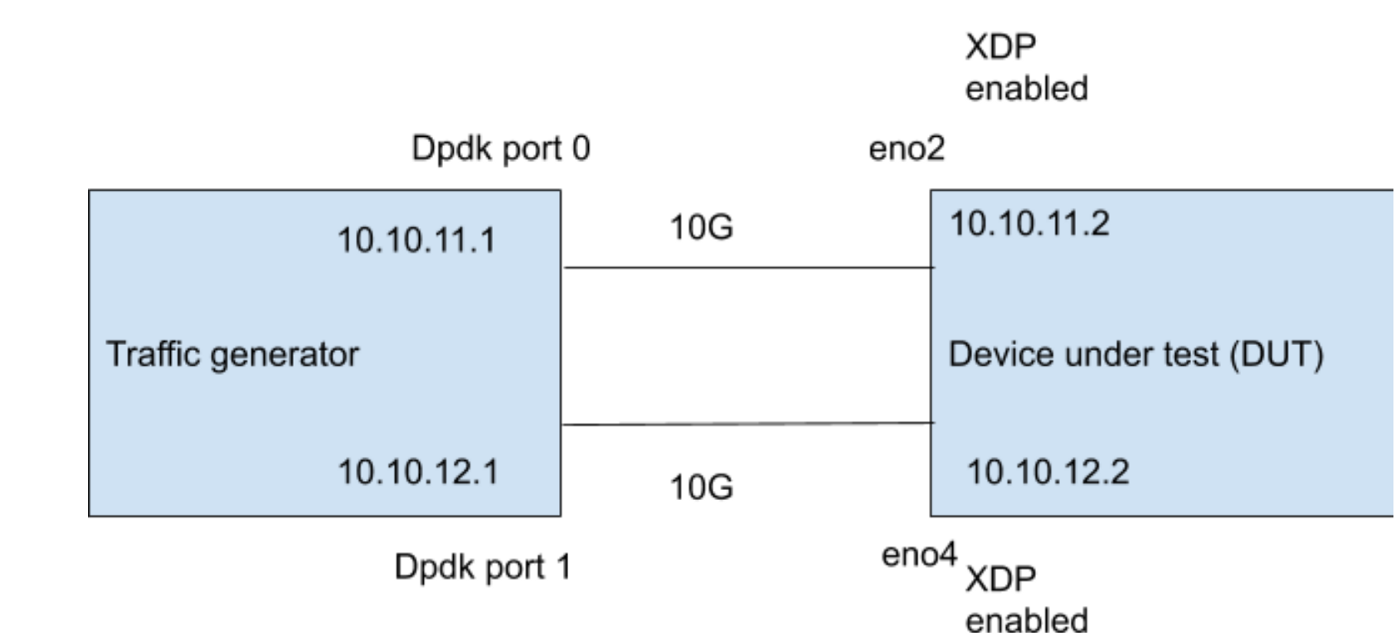

So far, so good, we’ve built an XDP based packet forwarder! For each packet that comes in on either network interface eno2 or eno4 it does a route lookup and redirects it to the correct egres interface, all in eBPF code. All in a hundred lines of code, Pretty awesome, right?! Now let’s measure the performance to see if it’s worth it. Below is the test setup.

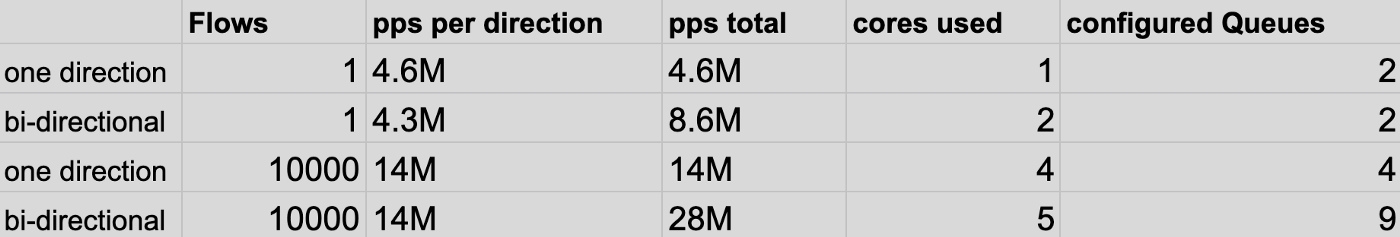

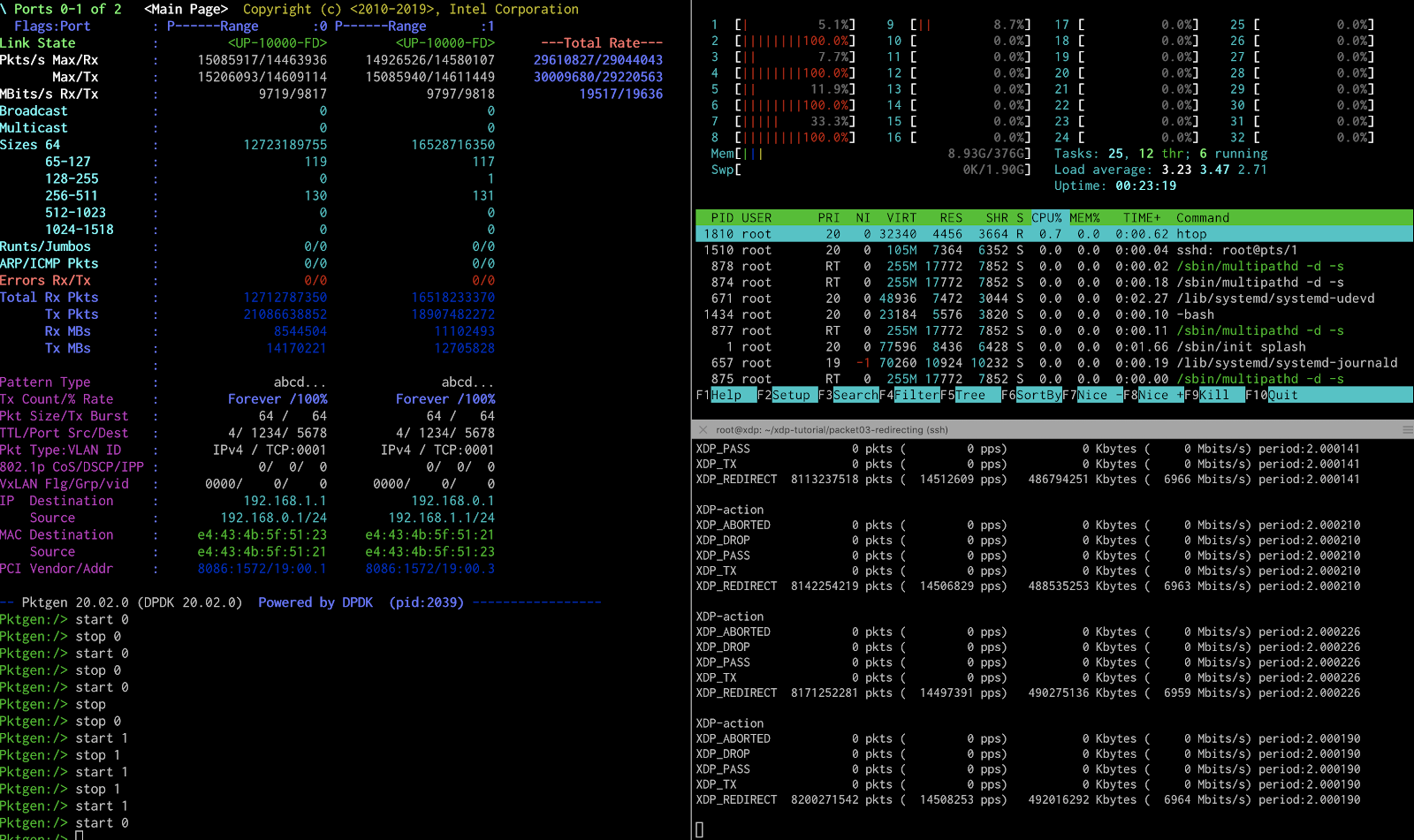

I’m using the same traffic generator as before to generate 14Mpps at 64Bytes for each 10G link. Below are the results:

The results are amazing! A single flow in one direction can go as high as 4.6 Mpps, using one core. Earlier, we saw the Linux kernel can go as high as 1.4Mpps for one flow using one core.

14Mpps in one direction between the two NICs require four cores. Our earlier blog showed that the regular kernel would need 16 cores to do this work!

Finally, for the bidirectional 10,000 flow test, forwarding 28Mpps, we need five cores. All tests are significantly faster than forwarding packets using the regular kernel and all that with minor changes to the system.

Just so you know

Since all packet forwarding happens in XDP, packets redirected by XDP won’t be visible to IPtables or even tcpdump. Everything happens before packets even reach that layer, and since we’re redirecting the packet, it never moves up higher the stack. So if you need features like ACLs or NAT, you will have to implement that in XDP (take a look at https://cilium.io/).

A word on measuring cpu usage.

To control and measure the number of CPU cores used by XDP, I’m changing the number of queues the NIC can use. I increase the number of queues on my XL710 Intel NIC incrementally until I get a packet loss-free transfer between the two ports on the traffic generator. For example, to get 14Mpps in one direction from port 0 to 1 on the traffic generator through our XDP router, which was forwarding between eno2 and eno4, I used the following settings:

ethtool -L eno2 combined 4

ethtool -L eno4 combined 4For the 28Mpps testing, I used the following

ethtool -L eno2 combined 4

ethtool -L eno4 combined 4A word of caution

Interestingly, increasing the number of queues, and thus using more cores, appears to, in some cases, have a negative impact on the efficiency. Ie. I’ve seen scenarios when using 30 queues, where the unidirectional 14mps test with 10,000 flows appear to use almost no CPU (between 1 and 2) while the same test bidirectionally uses up all 30 cores. When restarting this test, I see some inconsistent behavior in terms of CPU usage, so not sure what’s going on, I will need to spend a bit more time on this later.

XDP as a peering router

The tests above show promising results, but one major difference between a simple forwarding test and a real life peering router is the number of routes in the forwarding table. So the questions we need to answer was how the bpf_fib_lookup function will perform when there are more than just a few routes in the routing table. More concretely, could you use Linux with XDP as a full route peering router?

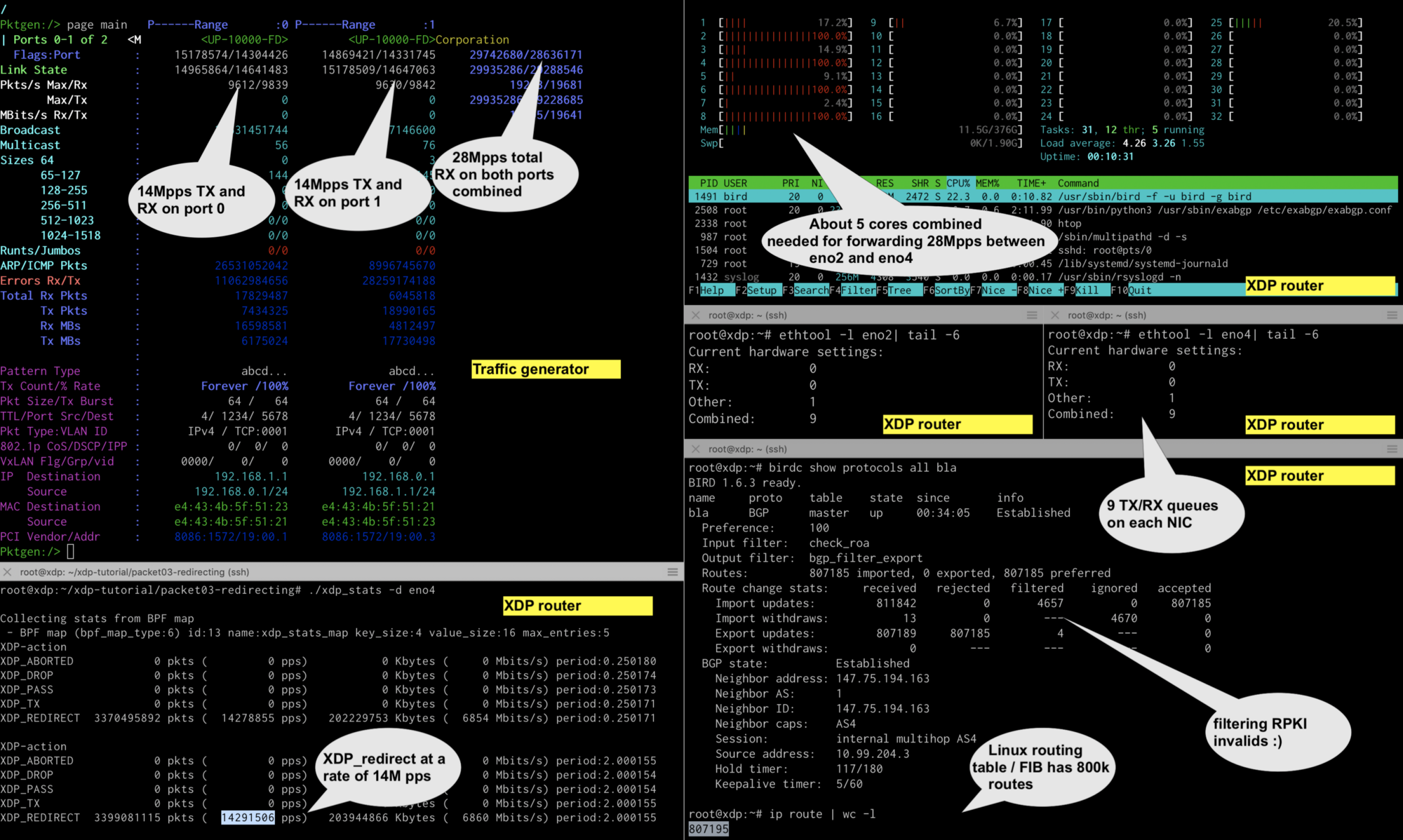

To answer this question, I installed bird as a bgp daemon on the XDP router. Bird has a peering session with an exabgp instance, which I loaded with a full routing table using mrt2exabgp.py and a MRT files from RIPE RIS.

Just to be a real peering router, I also filtered out the RPKI invalid routes using rtrsub. The end result is a full routing table with about 800k routes in the Linux FIB.

After re-running the performance tests with 800k bgp routes in the FIB, I observed no noticeable decrease in performance.

This indicates that a larger FIB table has no measurable impact on the XDP helper bpf_fib_lookup(). This is exciting news for those interested in a cheap and fast peering router.

Conclusion and closing thoughts.

We started the article with a quick introduction to eBPF and XDP. We learned that XDP is a subset of the recent eBPF developments focused specifically on the hooks in the network stack. We went over the different XDP actions and introduced the redirect action, which, together with the bpf_fib_lookup helper allows us to build the XDP router.

When looking at the performance, we see this we can speed up packet forwarding in Linux by roughly five times in terms of CPU efficiency compared to regular kernel forwarding. We observed we needed about five cores to forward 28Mpps bidirectional between two 10G NICs.

When we compare these results with the results from my last blog, DPDK and VPP, we see that XDP is slightly slower, ie. 3 cores (vpp) vs 5 cores (XDP) for the 28Mpps test. However, the nice part about working with XDP was that I was able to leverage the Linux routing table out of the box, which is a major advantage.

The exciting part is that this setup integrates natively with Netlink, which allowed us to use Bird, or really any other routing daemon, to populate the FIB. We also saw that the impact of 800K routes in the fib had no measurable impact on the performance.

The fib_lookup helper function allowed us to build a router and leverage well-known userland routing daemons. I would love to also see a similar helper function for conntrack, or perhaps some other integration with Netfilter. It would make building firewalls and perhaps even NAT a lot easier. Punting the first packet to the kernel, and subsequent packets are handled by XDP.

Wrapping up, we started with the question can we build a high performant peering router using XDP? The answer is yes! You can build a high performant peering router using just Linux and relying on XDP to accelerate the dataplane. While leveraging the various open-source routing daemons to run your routing protocols. That’s exciting!

Cheers

-Andree